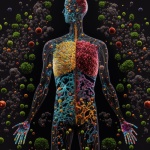

A diversified microbiome is a healthy microbiome

Our whole health care system is built around getting patents and selling patentable materials. You take X for your reflux, Y for your headache and Z for your allergies. All the research is built around single solutions for health problems. This is great if you are selling pharmaceuticals, not so great if you are trying to get people healthy.

The microbiome is linked to many health problems. Research has shown that gut bacteria can affect the brain.1 Bowel flora may also be involved with neurodegenerative diseases, like Parkinson’s.2

There is a connection between bowel ecology and depression.3-6 About 75% of the immune system is associated with the GI tract, so it is not surprising the microbiome can affect your resistance to viral and bacterial infection. There are several studies support ing this link. Probiotic supplementation (good flora) can support the immune system.7-9 Addressing the microbiome and leaky gut may be the best way to help patients with autoimmune diseases. According to studies, there is a connection between the severity of the disease and the makeup of the microbiome and the integrity of the intestinal lining.10-13 Both leaky gut and bowel flora imbalance are linked to allergies.14-20

In spite of the interest in this topic and the research, your patient will likely be told by his or her medical doctor there is nothing to “prove” that addressing the microbiome will help them. This is much the same way Ignaz Semmelweis was told there was nothing to prove that having surgeons wash their hands would cut down on post-operation mortality. So, you are likely to be asked by your patient, “Why are you treating my stomach to fix my allergies?”

Part of the problem is we ourselves use the medical model to explain what we are doing — and it is a mistake. Many of us have a green pharmacy approach to nutrition — “Take this herb and it will help your hay fever.” The reality is many things may not be functioning correctly in a patient with hay fever.

Emanual Cheraskin, MD, DMD, came up with a creative way to explain natural health care in the 1970s and published it in his book, Predictive Medicine.21 The patient needs to understand you are not treating their symptoms; you are fixing infrastructure.

“Cheraskin explains:

- If you have all the components of good health, like diet, structure, activity, etc., you are healthy.

- If you do something to undermine your health, like smoke, eat junk food, etc., enzymes are affected.

- If the situation continues, hormones are affected. For example, if you eat a lot of sugar, you become insensitive to insulin and your adrenal glands are affected.

- If the situation continues, it causes multiple problems with the body’s biochemistry.

- Eventually, physiologic performance is affected. This is the patient who feels “something is wrong,” but doctors are unable to find the problem.

- If the problems are not addressed, the patient develops signs (e.g., positive medical tests) and symptoms.

Disease develops when core health issues are challenged. Chemical toxins, poor diet, poor structural integrity, negative thinking and even genetics can undermine health and eventually lead to symptoms. Medicine focuses on controlling symptoms, which works well in emergency situations. Chronic health issues respond to efforts to restore health. For example, someone with asthma will improve when given magnesium. Magnesium does treat asthma — it treats a magnesium deficiency. Asthmatics respond because magnesium supports their core health issues. Natural health care addresses core health issues. It works to shrink the big blob in the last frame, causing it to shrink and the symptoms to abate. Treating symptoms may offer relief, but often those treatments undermine the center of the circle.”21

Closing thoughts

Teach your patients the importance of the microbiome. The intestines are an ecosystem. An individual has between 2-6 pounds of microorganisms in their intestines (according to the National Institutes of Health). There are more bacteria cells in the colon than there are cells in your entire body (bacteria cells are much smaller than your other cells). Chemical byproducts from intestinal bacteria have a powerful effect on health. Plus, over 70% of the immune system is associated with the GI tract. Bacteria are like little chemical factories. Good flora produce vitamins, heal the intestinal lining, break down toxins and suppress bad flora. Bad flora produce toxins, irritate the intestinal lining and suppress good flora. OK, that is an oversimplification. We all have some bad flora that is normal. It is offset by a large and diverse population of good flora. It isn’t always necessary to kill the bad flora (although in some cases of SIBO or IBS, that is a good strategy).

Make sure your patients understand the connection between diet and the microbiome. A diet of Coke and Cheetos will grow bacteria that feed on Coke and Cheetos. Taking probiotics and antimicrobials is useless without dietary changes. Avoiding processed and refined foods is vital. Patients need to eat food high in fiber and polyphenols (translated: vegetables), and they need to diversify their diet. A diversified microbiome is a healthy microbiome. Make patients understand their GI tract is either poisoning them or supporting health and immunity.

PAUL VARNAS, DC, DACBN, is a graduate of the National College of Chiropractic and has had a functional medicine practice for 34 years. He is the author of several books and has taught nutrition at the National University of Health Sciences. For a free PDF of “Instantly Have a Functional Medicine Practice” or a patient handout on the anti-inflammatory diet, email him at paulgvarnas@gmail.com.

References

- Wood AD, et. al. Patterns of dietary intake and serum c Gut Microbes. Br J Nutr. 2014;112(8):1341-52. Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-of-nutrition/. Accessed Sept. 19, 2023.

- Hegelmaier T, et. al. Interventional Influence of the Intestinal Microbiome Through Dietary Intervention and Bowel Cleansing Might Improve Motor Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease. Cells. 2020;9(2):376. PubMed website. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32041265/. Accessed Sept. 19, 2023.

- Park M, et. al. Flavonoid-Rich Orange Juice Intake and Altered Gut Microbiome in Young Adults with Depressive Symptom: A Randomized Controlled Study. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1815. PubMed website. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32570775/. Accessed Sept. 19, 2023.

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, et. al. Marital distress, depression, and a leaky gut: Translocation of bacterial endotoxin as a pathway to inflammation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;98:52-60. PubMed website. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30098513/. Accessed Sept. 19, 2023.

- Ramirez-Carrillo E, et. al. Disturbance in human gut microbiota networks by parasites and its implications in the incidence of depression. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):3680. PubMed website. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32111922/. Accessed Sept. 19, 2023.

- Maes M, et. al. The gut-brain barrier in major depression: intestinal mucosal dysfunction with an increased translocation of LPS from gram negative enterobacteria (leaky gut) plays a role in the inflammatory pathophysiology of depression. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2008;29(1):117-24. PubMed website. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18283240/. Accessed Sept. 19, 2023.

- Macalister Kinross J, et. al. A meta-analysis of probiotic and synbiotic use in elective surgery: does nutrition modulation of the gut microbiome improve clinical outcome? J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2013;37(2):243-53. PubMed website. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22750803/. Accessed Sept. 19, 2023.

- Li Ke-Liang, et. al. Alterations of intestinal flora and the effects of probiotics in children with recurrent respiratory tract infection. World J Pediatr. 2019;15(3):255-261.PubMed website. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31020541/. Accessed Sept. 19, 2023.

- Miller LE, et. al. Short-term probiotic supplementation enhances cellular immune function in healthy elderly: systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled studies. Nutr Res. 2019;64:1-8. PubMed website. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30802719/. Accessed Sept. 19, 2023.

- Chen YJ, et. al. Intestinal microbiota profiling and predicted metabolic dysregulation in psoriasis patients. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27(12):1336-1343. PubMed website. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30238519/. Accessed Sept. 19, 2023.

- Huang L, et. al. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota was closely associated with psoriasis. Sci China Life Sci. 2019;62(6):807-815. PubMed website. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30264198/. Accessed Sept, 19, 2023.

- Peltonen R, et. al. Faecal microbial flora and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis during a vegan diet. Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36(1):64-8. PubMed website. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9117178/. Accessed Sept. 19, 2023.

- Cignarella F, et. al. Intermittent Fasting Confers Protection in CNS Autoimmunity by Altering the Gut Microbiota. Cell Metab. 2018;27(6):1222-1235. PubMed website. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29874567/. Accessed Sept. 19, 2023.

- West CE, et. al. Gut microbiome and innate immune response patterns in IgE-associated eczema. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45(9):1419-29. PubMed website. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25944283/. Accessed Sept. 19, 2023.

- Laudat A, et. al. The intestinal permeability test applied to the diagnosis of food allergy in paediatrics. West Indian Med J. 1994;43(3):87-8. PubMed website. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7817543/, Accessed Sept. 19, 2023.

- Kovacs T, et. al. Relationship between intestinal permeability and antibodies against food antigens in IgA nephropathy. Orv Hetil. 1996;137(2):65-9. PubMed website. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8721870/. Accessed Sept. 19, 2023.

- Griffith CE, et. al. Intestinal permeability in dermatitis herpetiformis. J Invest Dermatol. 1988;91(2):147-9. PubMed website. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3397588/. Accessed Sept. 19, 2023.

- Ventura A, et. al. Intestinal permeability, atopic eczema and oral disodium cromoglycate. Pediatr Med Chir. 1991;13(2):169-72. PubMed website. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1910165/. Accessed Sept. 19, 2023.

- Myles IA, et. al. First-in-human topical microbiome transplantation with Roseomonas mucosa for atopic dermatitis. JCI Insight. 2018;3(9):e120608. PubMed website. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29720571/. Accessed Sept. 19, 2023.

- Drago L, et. al. Changing of fecal flora and clinical effect of L. salivarius LS01 in adults with atopic dermatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46 Suppl:S56-63. PubMed website. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22955359/. Accessed Sept. 19, 2023.

- Cheraskin E, Rinsdorf, WM. Predictive medicine. Keats Pub. January 1977.